“The only way out of the labyrinth of suffering is to forgive.” ~ John Green, Looking for Alaska

What is your difficulty?

What feelings arise?

How does it affect you?

What is your part or participation in the difficulty?

What are you learning about yourself, others, the difficulty?

What can you shift in your perspective about this difficulty?

How are you working with it?

How might you use what you learn from this difficulty?

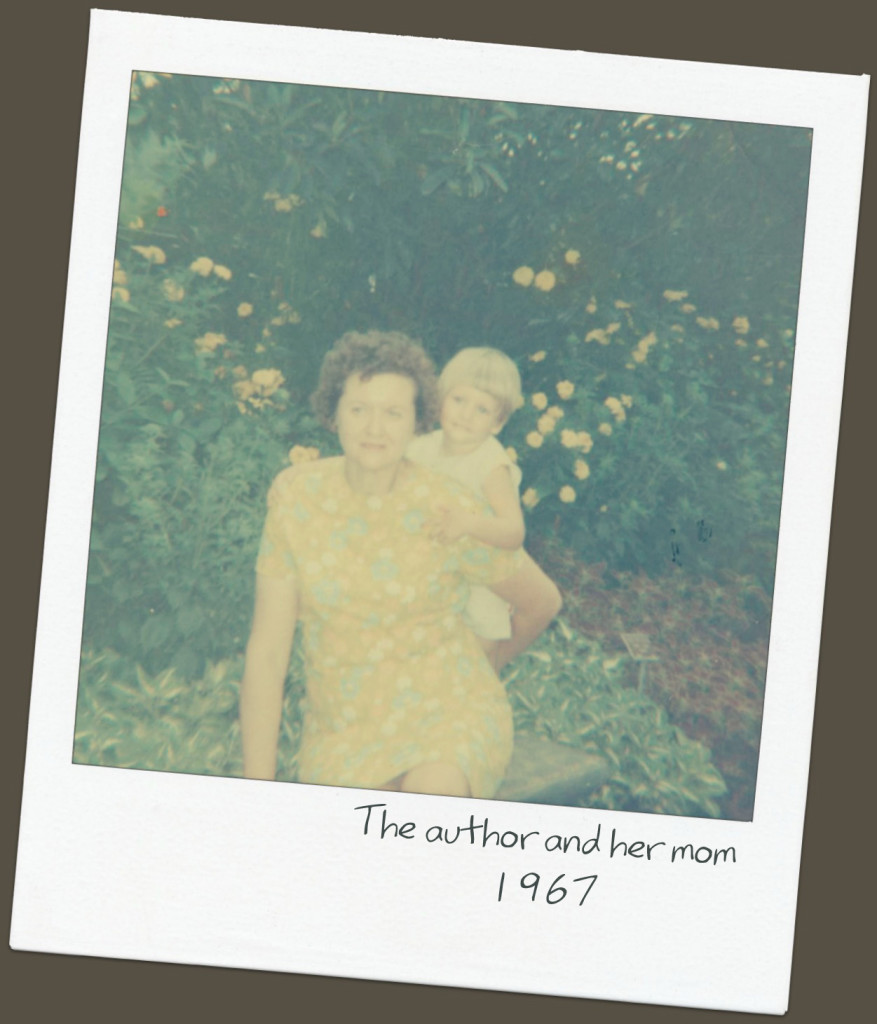

I was mad at my mom for a long time. Like three decades, I’m afraid to say. But that’s how long it’s taken me to truly understand her and forgive her through the eyes of understanding, compassion, and love. She died in the fall of 2013 after a ten-year journey through Alzheimer’s Dementia and often now, I think about what I’d say if I could bring her back. I think it would be, “ I finally get you.”

Her Story:

My mom, Mary Magdalene (yes, really) was born in Philadelphia in 1923, the daughter of Lithuanian immigrant parents and poor as can be. Her deep Catholic faith and hardscrabble history defined her. Looking for a way to help support her mom after her dad’s death, she entered the Air Force in 1952, a rarity for the men-driven times. Mid-tenure, she fell into a depression and sought treatment from the doctor on the base. He prescribed Thorazine, a popular anti-psychotic that caused horrible side effects. My mom was then sent to Walter Reed Medical Hospital in D.C. where doctors opted to treat her with electroshock therapy, a then-standard psychiatric treatment in which seizures were electrically induced into the brain for patients to provide relief from psychiatric illnesses. She was rightfully traumatized — and sought retribution for the “abuse” for the rest of her mindful life, sharing her story relentlessly with anyone and everyone, including sending letters to the community newspaper and the CIA. “What are you hoping for?” I’d ask, weary of her re-telling. “An apology,” she’d say. I was never certain from whom the apology would come; I simply wanted her to join me in our present life and help ME through my living hell in a way that told me she saw me as unique and separate from her own experience.

My Story:

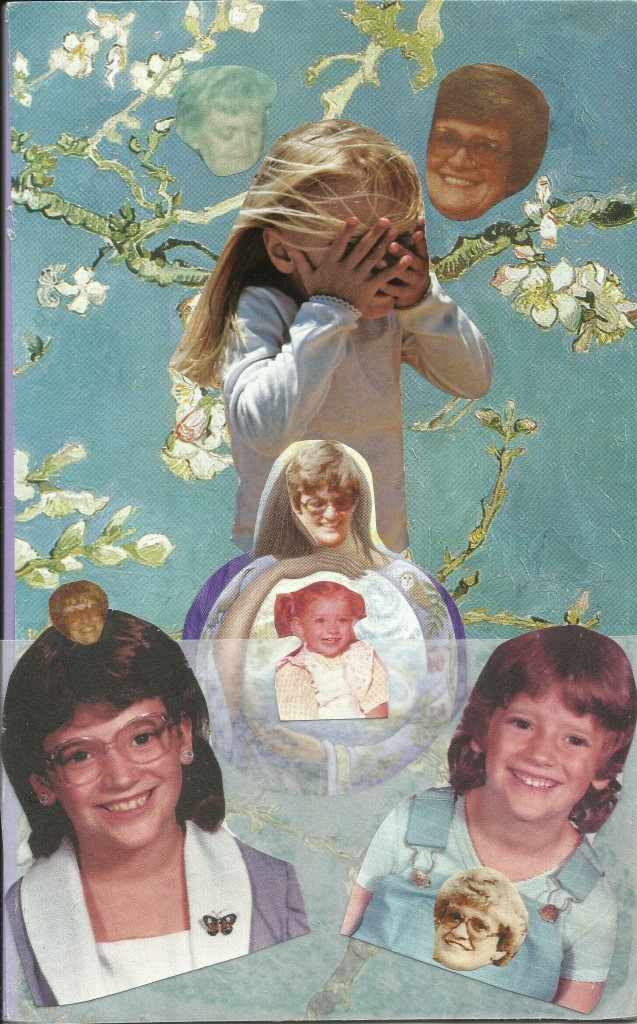

I was born in 1965, the single girl after two brothers. It is 1975, and I am 9 years old. On a random January day, in the cold Midwest, I had my first grand mal seizure. And just like that, I began a 15-year journey of fear. Two, three, four times a week, I’d have grand mal seizures, relenting to the unseen forces of my brain’s wayward electrical activity. At school. In the middle of the night. My mom, convinced her electroshock therapy had caused my seizures, steered clear of anything “medical” related, opting instead for a fruitless pursuit of homeopathic remedies that included chiropractic care, vitamins, and tinctures for “cerebral allergies. ” I felt abandoned as she allowed me to exist in utter terror of when the next seizure would strike. When a classmate had an epileptic seizure next to me in class, I went home and told my mom I had epilepsy and could take pills to control my seizures. “No you don’t,” she replied. “It’s your diet, and we’ll figure it out.” While I continued to have seizures, she cut out sugar in our family’s diet, upped our vitamin intake and served up millet for breakfast. And asked her Bible Study ladies to pray harder for a miracle. I just grew more angry toward her and her Catholic faith.

I went off to college and had the biggest seizure of my life in my dorm room. My roommate called 911 and just like that – I was diagnosed as an epileptic by the emergency room doctor and immediately put on Tegretol, an anti-convulsant. Hallelujah! I felt like God had finally shown up. I called my mom who, not surprisingly, tsk tsk-ed my decision to take meds. But I was done listening to her, relishing my ability at 18 years old to make my own medical choices. Fast forward a few more years and an MRI revealed a benign brain tumor (MRIs came into use in 1987) in the right parietal part of my brain — the cause of my seizures. I opt at the age of 26 to have brain surgery to remove it, interviewing doctors and treatment options on my own in Connecticut where I moved after college graduation. I told my mom she could come to my brain surgery if she wanted. She did, but I found no comfort in her presence there. My then boyfriend and now husband of 24 years had the caring covered.

Our Story:

My life journey continued into marriage and motherhood, and my mom was equally uninvolved. I had four children, and she and my dad had no relationship with them. I left the Catholic faith after my first baby, further driving a wedge between us. I deeply envied my friends and their moms and the intimacies between them. I spent countless hours in therapy over our non-relationship. She didn’t want to be part of my life, and I just couldn’t understand it. When I pointedly asked my mom about our history, i.e. “How could you have let me go through that, mom?” she would deflect, saying, “You don’t know what it’s like to have a hard-of-hearing husband.” Yes, my dad was hard of hearing. But what the hell did that have to do with me? My therapist told me she was incapable of a relationship because of her own damaged spirit. I felt 100% ripped off because I was a damn good person. Married to a wonderful man with four beautiful children. Nice and funny and loved by many. Who wouldn’t want to actively be my mom?!

And then in her mid 70’s, my mom got Alzheimer’s Dementia that took away her memories and hygiene. My brothers and I are called to journey with my parents through this circle-of-life reality. I didn’t feel like it, I reasoned through my resentment, “How convenient, I thought. First you are unavailable by choice and now because your mind is gone. Why should I help you when you didn’t help me?” But I couldn’t live with that version of myself, seeing her so helpless and mentally missing, soiling her clothes and floor and getting no help from my equally confused dad. So I come alongside her and them for a decade of decline, finally saying our final goodbye to both my parents in 2013. I felt sad when they passed, but more sad for the years gone by for the wonderful family memories that filled them.

The Transformation:

In my parent’s final years, I spent a lot of time reading through their personal histories, in journals kept by both of them and through various medical records left in folders. I connected many dots through conversations with cousins and my own maturing. I clearly see now how my mother laid her own “fear story” over my story. In her desire to protect me, she did anything but, transferring her trauma instead onto me. How different things might have been if she could have seen me as an individual with different needs and desires — and someone who wanted a voice and support in my own journey.

I am breaking the fear cycle in my own family by practicing vulnerability with my children. By explaining the why and how behind my behavior, thoughts and decisions, I can open the door to true intimacy, understanding, and deep connection — the exact opposite of what I experienced with my own mother. I am increasingly learning to look at people with compassion and curiosity versus critique and condemnation.

I am not angry anymore. I feel more compassion than bitterness toward my mom. I’m sad for what I missed out on. I grieve the loss of the mother/daughter relationship I never had. I feel, however, she is more available to me in heaven than she ever was on Earth. I find healing through my own close and connected family. I am writing a new story for myself — one of courage and transformation.